There

are events, sometimes small, that reverberate down through the years, sometimes

with unexpectedly momentous consequences (“For want of a nail …”).

This is not one of those.

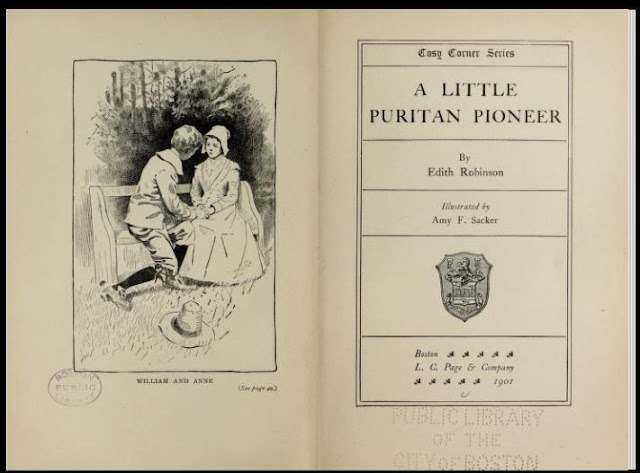

Rather, it’s the story of a misprint composed

by an unknown hand in a book published by the L.C. Page Company in 1901. The

misprint reappeared 111 years later in a personal name authority record

created by the Library of Congress in 2012, and briefly puzzled me, then sent me

down a "Little Puritan" rabbit hole when I stumbled on it in the Library of

Congress authority file 120 years after the misprint was first made. Uncharacteristically, this post is not

primarily about binding design; although to offset any disappointment it does

involve one of our favorite designers here at UNCG, Amy M. Sacker. Instead, it’s about a binding designer in the

role of illustrator--or is it?

Here’s a visual statement of the puzzle:

Before

we get into a discussion of the book, let’s step back for a moment and consider

cataloging and authority control. In our

work cataloging Special Collections materials we use the bibliographic utility

OCLC. Headquartered in Dublin, Ohio,

OCLC describes itself as “a global library cooperative that provides shared

technology services, original research, and community programs to libraries,

including our 18,000 members in 120+ countries.” As of December 2021, OCLC includes a

database, WorldCat, of over 520 million catalog records and over 3 billion holdings.

As part of our work

we frequently contribute to the database of authority records maintained by

OCLC, either by creating new authority records or editing and improving

existing records. Authority

records exist to provide an “authorized” form of name by establishing it in a unique

form to unambiguously identify persons, corporations, families,

geographic names, subjects, titles, genres, etc. The purpose, with personal names for example,

is twofold: to ensure that all works by a person are gathered under a unique

authorized form, and to differentiate each name so that works by other persons

are not attributed incorrectly. These

authorized headings are then used in cataloging and ideally make searching and

identifying more effective for everyone by gathering everything

by a given person under one form of name while excluding materials by other

persons.

For

myself, one of the benefits of the authority file is that it allows me to

quickly find an authorized form of name (if one exists) and cut and paste the

coded form of the heading into the catalog record on which I’m working. A short time ago I was cataloging a book with

a binding by Amy Sacker and wanted to add her name to the catalog record as the

binding designer. Browsing the authority file gave me this hit list:

For whatever reason (though I like to think that it was deep concentration on the task at hand), what I had

not noticed before was that there was another entry, one for an “Amy F. Sacker”

with the same dates, in addition to “Amy M. Sacker” in the browse search results. As far

as I knew, as with the Highlander, “there can be only one” Amy Sacker and I was

intrigued by this second Sacker. [1]

When I selected the record for Amy F. Sacker I encountered the following:

|

| Library of Congress Authority File record for Amy M. Sacker |

This is the public display of the authority

record from the Library of Congress authority file. Note that “Sacker, Amy F.” etc. is under the

Variant(s) label on the Amy M. Sacker record, indicating that it is an unauthorized/unused

variant for Amy M. Sacker. If it was an authorized variant of the name that could be used on catalog records, it would appear under a “See also”

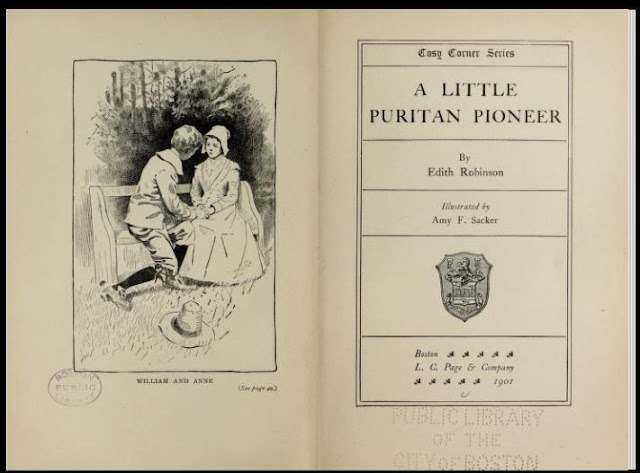

label. The source of name note (“Found

in”) indicates where the variant name appeared, in this case on the title page

of A Little Puritan Pioneer by Edith A. Robinson, published in 1901. So, apparently a misprint, though an odd one

as “F” and “M” are not in close enough proximity to routinely make such an

error, whether in a printer’s type cases or on a monotype keyboard (though the M does appear directly above the F on a linotype keyboard). Whatever was happening, this needed some

follow-up.

From OCLC, I found 2 records for A Little Puritan Pioneer, the first for

an electronic book with Amy F. Sacker given as illustrator. The second was for the 1901 print copy, which

we held. Then came another surprise; the

print version gave the illustrator on the title page as “A.F. Schmidt”!

There was no record for a print version of the book with Sacker as

illustrator in OCLC. It seemed certain

that the Sacker title page was in error, at least about the “F.” initial, but I

wanted to try and determine what had happened, so I turned to the illustrations, which seem clearly to be by another hand.

There are five full page illustrations and a further five in the text,

all of them signed “A F S” in script, which would fit with either Schmidt or a misprinted

Amy F. Sacker.

|

Illustration on page 19

|

|

| Illustration on page 5 |

|

| Illustration on page 57 |

|

Illustration on page 63

|

|

| Frontispiece |

|

| Monogram on frontispiece |

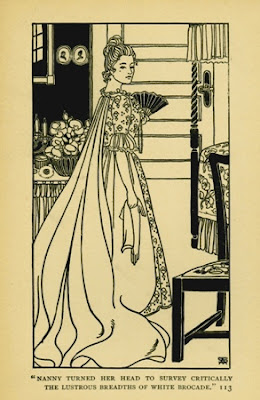

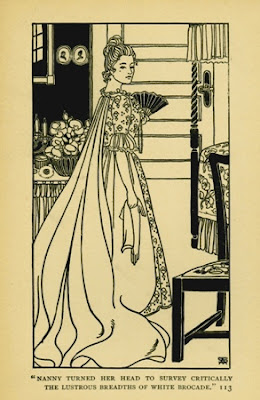

However, the style of the illustrations and the monogram clearly rule

them out as Amy M. Sacker’s work, as can be seen from authentic Sacker

illustrations:

|

Sacker illustration--A Little Puritan Rebel

| | Sacker illustration--A Little Puritan's First Christmas |

|

|

| Amy Sacker illustration--A Loyal Little Maid |

|

| Sacker illustration--A Little Daughter of Liberty |

We have already seen from the image of the

title page of A Little Puritan Pioneer, given above, that “Amy F. Sacker” was credited by the publisher--at least at one time--with the

illustrations, though this is in error.

To

add another wrinkle to an already wrinkly situation, the contents and illustration

pages have headpieces that were designed by Amy Sacker and have her monogram.

These headpieces were frequently

used in other books. Mark Schumacher, our

former colleague and Amy Sacker expert, lists 69 titles on his Amy Sacker Site where one or both designs were used, including many in L.C.

Page’s Cosy Corner Series (more on this series below). [2] So in a sense, Sacker did make a

contribution to illustrating the book!

I went to Publishers’ Weekly searching for more information on this

title since I was curious whether Amy Sacker was given as the illustrator in

advertisements for the book. The first

mention I located was in the July 13, 1901 issue, where it appeared in a “Record

of Series” and was listed with nine other titles in the Cosy Corner Series

published by the Boston firm of L.C. Page & Co. The Sept. 28, 1901 issue

includes a full page advertisement on p. 676 for “[t]en new volumes in the Cosy Corner Series of Charming Juveniles … [T]his series shall contain only the very

highest and purest literature—stories that shall not only appeal to the

children themselves, but be appreciated by all those who feel with them in

their joys and sorrows---stories that shall be most particularly adapted for

reading aloud in the family circle. The numerous illustrations in each book are

by well-known artists, and each volume has a separate attractive cover design.” Unfortunately, there is no mention for any of

the volumes of whom the well-known artists might be. As for the cover designs, attractiveness lies

in the eye of the beholder, with designs ranging from A Bad Penny, quite

attractive and designed by Alfred Brennan, with his monogram, to A Little

Puritan Pioneer, for me the least attractive of the lot. [3]

|

| "AB" monogram of Alfred Brennan |

I then checked the Library of Congress Copyright Office’s Catalogue of

Title Entries of Books and Other Articles.

Here the title was briefly described and included a statement that it

was illustrated by Amy F. Sacker, with a copyright date of Sept. 3, 1901, which

was also the date when two copies were received by the Library of Congress. [4].

As

I noted above, there was not a record for a print version of A Little Puritan Pioneer with Amy

F. Sacker as illustrator in OCLC. This

is not particularly surprising, since cataloging rules and interpretations have

changed many times over the years, and in older cataloging illustrators, for

example, were often not transcribed as part of the catalog record. I did wonder at what time the illustrator error

had been noticed and corrected. Although the error made it through the entire

publishing process, from copy editing through proofing and printing, I

suspected that not many copies with the error had made their way into

circulation before it was corrected. Some

of the eight institutions holding copies on the “Schmidt” catalog record might

actually have Sacker on the title page, but I only knew of three copies that were

definitely extant, two of which are held by the Library of Congress. The copy from which the digitized version was

made is held by the Boston Public Library, as shown by their ownership stamps.

It also

made sense that the Boston Public Library held a copy of the earlier issue or state since

L.C. Page was a Boston publisher and they probably acquired their copy shortly

after publication. In fact, one copy (their catalog lists two) was a gift from

the publisher, noted on their bookplate on the front pastedown, with an

additional handwritten date, Oct. 3, 1901, on the verso of the title page.

It is possible to speculate from this admittedly slim evidence that only

a few copies survive with the Sacker misprint.

Through

a strange coincidence, while I was looking into this title a second copy of the

book was donated to the UNCG Library by Mark Schumacher with an “Amy F. Sacker” title

page. Did I need to revise my original

supposition about the prevalence of the Amy F. Sacker issue? Perhaps the misprint existed for a longer

time, and more copies of the book were sold with the misprint after all.

The

Publishers’ Weekly advertisement of September 28, 1901 describes the ten Cosy

Corner Series volumes as large 16mos (sextodecimos).

Our well-loved copies of both the Sacker and Schmidt issues make an

examination of the books’ structures quite easy. Each consists of six gatherings of eight leaves

(16mo in 8s), with the Sacker issue made up of [10], 74, [12] pages, and the

Schmidt issue [10], 74, 10, [2] pages.

The Sacker issue has an advertisement on the half title page verso (p.

[2]) for “Works of Edith Robinson” listing five titles including A Little Puritan Pioneer, and [12] pages of advertisements at the end. The Schmidt issue half title page is blank

with 10, [2] pages of advertisements at the end. In both issues the advertisements are not

inserted but are printed as part of the final gathering of 16 pages. The advertisements at the end of the volumes

vary considerably. The Sacker issue

contains: full page advertisements for “new juveniles” (p. [1-7]), including three of the ten Cosy Corner titles listed in Publishers' Weekly, the first four volumes in the Little Cousin Series, and seven others; “Cosy Corner Series of Charming Juveniles” (p.

[8-11]) with 39 titles listed, not including the three volumes in the full page ad;

and four titles in the “Gift Book Series for Boys and Girls” (p. [12]).

The

Schmidt issue contains ten pages of advertisements for the Cosy Corner Series, listing 56 titles including all of the Cosy Corner cohort listed in the Publishers' Weekly advertisement and eight additional titles. The layout of

the series ads is completely different; they are in a different and larger font, with most of the ads arranged under

author headings, and with much lengthier

descriptions.

|

Cosy Corner ads--Schmidt version

|

|

| Cosy Corner ads--Sacker version |

Pages [11-12]

advertise the Little Cousin Series, the first four volumes now listed as “first

series” with an additional option for purchasing them as a boxed set. Page [12] announces six additional volumes as

a second series.

All this helps to establish the date when the Schmidt

version was issued, in this case 1902.

All of the new Cosy Corner titles that I can find in OCLC are copyright

1902, although some apparently have title page dates of 1903. Some of them represent digitized versions

that confirm the 1902 date, and three titles are digitized from the Library of

Congress and are stamped as received in May, June, or July 1902. Similarly, while the first four volumes of

the Little Cousin Series--the only titles in the Sacker issue--are all

copyright 1901, with one stamped as received by the Library of Congress July 26,

1901, the next six volumes, the “second series,” are all copyright 1902, with

digital versions of four of them stamped as received by the Library of Congress on

June 30, 1902.

To

answer the question posed above, unless some intermediate copy with different

ads is found, it appears that the Sacker issue persisted until it was partially

reset with the title page corrected to “A.F. Schmidt,” the list of Edith

Robinson titles omitted on the half title verso, and a new set of

advertisements replacing the ads on the final 12 pages of the last gathering of 16 pages,

dating to sometime in mid-1902. Presumably,

if there were any errors in the text of the work these would also have been

corrected in the Schmidt issue, though I haven’t gone so far as to check

this! With some confidence, we can

therefore state that the A.F. Sacker issue was published in 1901 and the A.F.

Schmidt issue was published in 1902. We

can also speculate that numerous copies of the misprinted issue might have

circulated in 1901 and early 1902, and only when further copies surface can

this be proved or disproved. The fact

that only eight libraries have added holdings to the OCLC record for this title

makes the possibility of numerous other copies appearing seem unlikely. Of course,

there may be copies of the Sacker issue extant but with a cancel title page

with Schmidt as illustrator, but that situation remains speculation until such

a copy is discovered.

Much

has been said here about the A.F. Sacker vs. A.F. Schmidt title pages, but that begs

the question: who was A.F. Schmidt? To

answer this, I first searched OCLC with no results, then turned to an old

standby, Who Was Who in American Art, 1564-1975. Though no A.F. Schmidt was

listed, I did find a cross reference from Albert Felix Schmidt to Albert F(elix)

Schmitt. Schmitt was a painter, born in

Boston in 1873, who studied at the Massachusetts Normal Art School, the Cowles

Art School in Boston, and the School of the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, where he

was considered a top student and was “regarded as one of the finer proponents

of the Boston School style of painting” [5]. He was one of the creators of what became the

early Boston Modernist Style. He was

offered the post of the court painter for the Vatican, which he accepted. He spent the rest of his life in Biarritz,

France, where he died in 1953 [6]. Although interesting, this doesn’t definitively answer if A.F. Schmidt is the same person as Albert Felix Schmitt.

Schmitt was a painter

who worked in oils and watercolors, whereas the illustrations in The Little

Puritan Pioneer are drawings. We

do have some examples of Schmitt’s work in two other

titles we hold: Louisa May Alcott’s May Flowers (Boston: Little Brown, 1899)

and Clara Louise Burnham’s Jewel’s Story Book (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1904),

but these seem to be reproductions of paintings.

|

| Jewel's Story Book: "I hear a sheep" |

|

| A.F. Schmitt--frontispiece, Jewel's Story Book |

|

| A.F. Schmitt--May Flowers |

In addition, only signatures rather than monograms are used.

|

| May Flowers--signature |

|

| Jewel's Story Book--signature |

An exhibition of his work at the Boston Art Club in 1921 lists

and illustrates only oil paintings and watercolors, which are also signed Albert F. Schmitt rather than monogrammed. [7]

|

| The White Vase |

|

| On the Piazza |

|

The White Vase--signature

|

|

| On the Piazza--signature |

None of this

precludes all the illustrations being from the same hand, but without further

evidence I must consider the identification probable but tentative. Perhaps the publisher requested drawings, or Schmitt was

trying his hand at illustrations in a different medium but wasn’t sure how favorably

they would be received. The choice of

the alternate spelling “Schmidt” and the use of a monogram may have been an

effort to lightly disguise the illustrator’s identity. Or there might actually have been another artist named A.F. Schmidt. [8]

As a sidenote, I note with pleasure that in

one of the books, Alcott’s May Flowers, the Schmitt and Sacker combination comes

full circle--not as a Schmidt/Sacker amalgam, but rather as contributors of the

illustrations and the binding design, respectively!

|

| Sacker cover. Attribution by Mark Schumacher |

I

was able to find almost no information about Edith Robinson, other than she was

born in Boston, Mass. on February 17, 1858, the daughter of George and Sarah

Louise Robinson, and was educated at the Girls’ High School in Boston. [9] She was the author of 11 books, 10 of them for

children. In addition to the Little

Puritan books she also wrote Forced Acquaintances: a Book for Girls (Boston:

Ticknor and Company, 1887) [10]; Penhallow Tales (Boston: Copeland and Day, 1896),

the lone non-juvenile title; and, The Captain of the School, illustrated by

Alice Barber Stephens (Boston: Little, Brown & Company, 1901).

A

final question that remains is why did “A.F. Sacker” get onto the title page of

The Little Puritan Pioneer in the first place?

While this can probably never be answered definitively, I do think that there’s

a clue in the publication history of Edith Robinson’s Little Puritan books. Edith Robinson wrote eight Little Puritan

books between 1896 and 1905, with a compilation of four of these titles

reissued in 1931. All of them were

published by L.C. Page and Company in their Cosy Corner Series. The University of North Carolina Greensboro

Special Collections has an extensive Girls Books in Series Collection and holds

all of these titles, though not all are first editions. These titles in

chronological order are: 1) A Loyal Little Maid (1897, c1896), with binding

design and illustrations by Amy Sacker [11]; 2) A Little Puritan Rebel (1898),

with an unsigned binding design attributed to Sacker in a contemporary

advertisement and illustrations by Sacker; 3) A Little Daughter of Liberty

(1899), with binding design by Alfred Brennan and illustrations by Sacker; 4) A Little Puritan’s First Christmas (1900), with unsigned but attributed binding

design and illustrations by Sacker; 5) A Little Puritan Pioneer (1901), with

illustrations by A.F. Schmidt; 6) A Puritan Knight Errant (1903), with a

binding design by “MH” (unidentified) and illustrations by Lewis Jesse

Bridgman; 7) A Little Puritan Bound Girl (1904) and 8) A Little Puritan Cavalier (1905), both with illustrations by Etheldred Breeze Barry.

|

| Amy Sacker cover 1898 |

|

| Amy Sacker cover 1897 |

|

| Alfred Brennan cover 1899 |

|

| Alfred Brennan monogram |

|

| Amy Sacker cover 1900 |

|

Sacker as illustrator version 1901

|

|

| 1904, c1903 |

|

| "MH" design 1903, c1902 |

|

| 1905 |

The compilation, Little Puritan Stories (Pioneer, Christmas,

Bound-Girl and Rebel), was reissued with the original illustrations in 1931.

The

series ran from 1897 through 1905, with a new volume appearing annually except

in 1902. I find it significant that the first four titles were illustrated by

Amy Sacker, and she is so credited on the title pages.

As noted above, she also provided the binding

designs for three of the titles, although only one, A Loyal Little Maid, carries her monogram.

So, with four already published titles associated with Sacker, one

might assume that the next volume would also include her distinctive style of

illustrations. But perhaps she was unavailable

due to commitments to other projects or had lost interest in continuing with

this series. Gullans and Espey note that this flagging of interest often happened

with binding styles established by Margaret Armstrong for individual authors

including Paul Bourget, Henry Van Dyke, John C. Van Dyke, Mary Raymond Shipman

Andrews and, perhaps most famously, Myrtle Reed, with later bindings designed

by other artists [12]. Presumably Armstrong was not the only artist to turn

to other, more rewarding work. L.C. Page

might have wished to go in another direction with the illustrations too. But through force of precedent, an illustrator’s name with some similarity to A.M. Sacker, a rush to get this book

out, or any number of other explanations—speculations are free!—Schmidt became

Sacker, at least briefly.

Or

perhaps L.C. Page just goofed. There is

intriguing evidence that this might have been the case, and it comes from two later volumes in the Little Puritan Series: A Puritan Knight Errant, and A Little Puritan Cavalier. I mentioned

above that although we hold all the titles in this series, all are not first

printings, one of these being A Puritan Knight Errant, which we have in 1906

and 1908 printings only. The cover

design by “MH” pictured above is actually from a digitized copy of the first

printing (1903) held by the Library of Congress.

There is no indication that this title is in the

Cosy Corner Series, either on the cover, preliminaries or among the eight pages of

advertisements at the end of the volume, and the catalog record indicates that

the book is 21 cm tall. L.J. (Lewis

Jesse) Bridgman is identified as the illustrator, and the illustration facing

page 104 is signed with his monogram.

Apparently,

Page wished to also issue this title (or they neglected to do so with the first

printing) along with the other Little Puritan books in the Cosy Corner Series. One of our copies, the fourth

impression, July 1906, is in the Cosy Corner Series (stated on the cover and

new title page, though not in the ads at the front or back of the volume). The book measures 18.3 x 12.9 x 1.8 cm. But with either the fourth, third, or second

impression--whenever the new Cosy Corner format was introduced—a double error

was also introduced:

Oops!

And here are the title pages from the 1903 and 1906 printings. Note the illustrators:

Oops … again!

We can speculate that Page, wishing to publish the Knight Errant in the

new format and reduced size, reused the cover of the last book published in the

series, A Little Puritan Cavalier, first published in June, 1905 (our copy is a

second impression, April 1910), rather than having to reduce the size of the die

by at least 1.3 cm. or commission a new image. Close counts, right?

We can hope that the title page error for the illustrator is simply

because they forgot, and not that they just didn’t care. Whatever the explanation is, the Puritan Knight Errant is "errant" by either of its definitions. A final oddity can be seen with our 1908 printing, which states on the

title page verso “Published, August, 1902; fourth impression, June,

1908.” (And another oddity, remember that our smaller Cosy Corner version was also called the fourth impression, but is dated July, 1906!)

With

this printing we’re back to the larger format and original binding design by “MH.” The book is now in the “Princess Series” (20.3

x 13.8 x 3.3 cm., on heavier paper with wider margins), with a new title page to

reflect this (the 1903 printing shows no more evidence of this series

than it does the Cosy Corner Series), and the series title also on the cover.

The larger format

Princess Series (titles generally 21 cm tall) was established by 1908 with its uniform illustrated

title pages. Perhaps Page wished to make the

Puritan Knight Errant available in both series to maximize sales as both seem to

have been quite successful, judging from the number of titles issued in each. This seems possible, as an advertisement

in the Feb. 29, 1908 issue of Publishers’ Weekly (p. 917) for the “The Princess Series of Copyright Fiction for Girls” notes that the series was inaugurated

in 1907 with 13 volumes, and that a further 12 titles were added due “to the demand

for high class copyright fiction for young girls at a popular price together

with the handsome appearance of the books themselves.” The original 13 volumes are listed in the

Sept. 28, 1907 issue, the first appearance of the series in Publishers' Weekly. The Puritan Knight Errant appears in the Jan.

26, 1907 issue, but only as part of the Cosy Corner Series; however in the Sept. 26,

1908 issue it appears as part of the Princess Series, along with the 11 other 1908

titles. The title first appears in 1902 and 1903, but not as part of any Page

series; it then reappears in the Sept. 15, 1906 issue where it is described as “First

published in 1902. Now included in the Cosy Corner Series”--with illustrations

by L.J. Bridgman. It would be interesting

to see if any copies of the Cosy Corner version are out there with the illustrator

corrected from Etheldred Barry to Bridgman on the title page.

Before closing this post, we should take at least a brief look at the

binding design on A Little Puritan Pioneer.

As mentioned above, I consider this the least effective of the 10

designs in this installment of Cosy Corner Series books (images of the

remaining nine designs are included in footnote three). The library holds two copies of the book; the

first is the 1901 issue with the “Amy F. Sacker” misprint and is bound in dark

yellow calico-texture cloth. The second has

the corrected title page and is bound in olive gray calico-texture cloth.

|

| 1901 issue with Sacker title page |

|

| 1902 issue with Schmidt title page |

Since the Boston Public Library copy with the misprint is bound in olive

gray cloth, we probably should not make much of the color difference. Perhaps the yellow cloth issue came first and the Boston Public copy came from a later binding run that continued into 1902, but this is only speculation. Both issues are stamped in reddish-brown, green, blue, yellow and black, and the background sky appears to have once been stamped in another color, perhaps white, cream or gray, but time and use have made it impossible to tell on any of the three copies.

|

| Boston Public Library 1901 issue with Sacker title page |

There is one difference in our two copies that shows that some work was done on the binding stamps between the first and second issues. When put side by side it is very clear that a larger size font was used for the author's name on the spine. Was this change made as part of the reissue of the book with a corrected title page? Or was it made as a separate correction of the binding only?

Our copy of the 1902 issue also has a registration error on the cover, with the dark green of the trees at upper left stamped too far to the left, leaving the right side uncolored. Is this a sign of a hasty reprinting? Neither of the 1901 copies show this error.

The binding design itself is chiefly a crude rendering of the Schmitt illustration on page 27.

The figures in the canoe are particularly bad--even disturbing--with the young girl looking not at the almost featureless man paddling the canoe, but out at us from under a swathe of blue cloth. Her face looks more like a cutout, as faces often looked in the cheap woodcuts used to illustrate children's books in the previous century. It's a marked drop off in quality from the previous four titles in the series and a low point in the series. Once again, I wonder why, after using well-known artists for the first four books, this choice was made by L.C. Page.

Schmitt's original illustration appeared in the second chapter of the book with the intriguing title "The Crab." After a quick glance through the early pages of the book, I discovered that the canoeing scene was not a casual paddle across a lake but was actually the culmination of a rescue from what seemed to be a monstrous crab. The girl, Anne Chilton, while searching for fresh water on a shunned peninsula for her feverishly sick mother and brother, wanders into a wide marshy area. This region, legend had it, was the home of a giant killer crab. As the tide comes in she finds herself in what seemed to be ribbed sand in long tentacles with claw-like extremities. Suddenly the claws stir and it seems "all about her the tentacles were waking into horrid life … She had rushed into the very danger from which she fled, and was standing upon the back of the Crab!" A hermit hears her cries and paddles to the rescue, pulling her into his canoe. "The water was over the spot she had just quitted, and, as in a nightmare, Anne saw the crab rise to the surface, and stretch out long, waving arms after its escaping victim."

Now THAT would make a great cover design!

(And spoiler: it wasn't a crab). [13]

References

[1]. Many thanks to my daughter who made the edited Highlander/Sacker image, mercifully replacing the one I originally put together.

[2].

Sacker headpieces for contents and

illustrations appear on 69 titles, almost all of which are on publications by

Boston publishers L.C. Page or Joseph Knight. Other Boston publishers using

these designs were: Ginn & Co. (one title); Little, Brown (six titles);

Houghton Mifflin (three titles); Oliver Ditson (one title), and Charles Goodspeed (one title). New York publishers using them

are Caldwell (one title), and A. Wessels (one title). Thanks to Mark for the many images used from his website. Other images from UNCG's American Publishers Trade Bindings digital collection and the Internet Archive.

[3]. The 10 titles listed in the advertisement for the Cosy Corner Series are: 1).

A Little Puritan Pioneer;

2). Frances Margaret Fox, Betty of Old Mackinaw; 3). John T. Wheelwright, A Bad Penny, with the monogram of the designer, Alfred Brennan;

4). Louise de la Rame (Ouida), Findelkind;

5). Mrs. Ewing, Madam

Liberality;

6). Frances E. Crompton, Gatty and I;

7). A. Comyns Carr, The Fairy of the Rhone;

8). E. Livingston Prescott, A Small, Small Child;

9). Mary Knight Potter, Peggy’s Trial;

10). Frances Hodges White, Aunt Nabby’s Children.

[4]. Volume 29, 4th quarter, 1901, p. 397. Note that the copyright entry describes the book as a 12mo as opposed to the publisher's description of the series as a large 16mo, the difference being that the Library of Congress described the book according to a standard size for a duodecimo, 7 3/8 x 5 inches (19 x 13 cm) rather than by format.

[5]. Who Was Who in American Art, 1564-1975. Sound View Press, 1999, p. 2928. askART,

Albert Schmitt, Biography from The Boston Art Club, viewed March 24, 2022.

[6]. askART. "Albert Schmitt."

[8]. There are entries in Who's Who in American Art, v. 4, 1940-1947, for both a painter, Albert Felix Schmidt, living at 556 West 156th Street, New York City; and an illustrator, Felix Schmidt, at 232 East 40th Street, New York City. While the former is almost certainly our "Schmitt", no further information is given about either.

[9]. Woman’s Who’s Who of America. Edited by John William Leonard. New York:

American Comonwealth Co., 1914- Vol. 1914/15, page 694-695.

[10]. Forced Acquaintances was reprinted: New York: R.F. Fenno & Co., [1902?] as

no. 18 of the Summer Series, and New York: H.M. Caldwell Company, [1907?] in

the series Famous Books for Girls, new edition, 1907, no. 18.

[11]. The first book in the Little Puritan Series, A Loyal Little Maid, was copyright 1896 by Joseph Knight Company, and a digital version

of the Library of Congress copy has a title page with Joseph Knight as

publisher and a date of 1897; this title page also has a copyright stamp dated

August 31, 1896. In 1897 The Joseph Knight Company became L.C. Page & Company when the brothers L.C. and G.A. Page, both employees of the Joseph Knight Company, took over the business.

Our copy with L.C. Page

& Company on the title page is dated 1897 with an 1896 copyright on the

title page verso. Although there is an

OCLC record that indicates that a version exists with the title page dated

1896, I have not seen either a printed or digitized version with 1896 rather

than 1897 on the title page. It should be noted that the Library of Congress

catalog record, from which the OCLC record purports to be transcribed, gives

the date as 1897 in LC’s online catalog.

[12]. Gullans, Charles

and John Espey, Margaret Armstrong and American Trade Bindings, UCLA, 1991, p.

28.

[13]. The "Crab" turns out to be quicksand.